Here are ten reasonably challenging problems on powers and roots. Solutions follow the problems. Remember, no calculator!

Statement #1: x < 1

Statement #2: x > –1

- 4

- 8

- 14

- 28

- 42

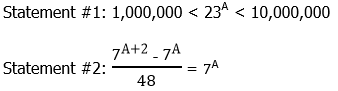

5) If A is an integer, what is the value of A?

- 11

- 30

- 45

- 75

- 225

Powers & roots

This is a tricky set of topics. Here are some previous blogs I have written about these ideas:

2) Patterns of powers for different kinds of numbers

3) Adding & Subtracting Powers

4) Roots

If you read one of those articles and have some insights, you may want to give the problems above another glance. If you would like to clarify anything said here or in the solutions, please let us know the comments section.

Practice problem explanations

1) For positive numbers less than one, when we raise them to positive integer powers (square, cube, etc.), then get smaller, further from one. When we take roots of them (square root, cube root), they get bigger, closer to one. The higher the root, the closer it is to one. Thus, for any x in the 0 < x < 1 range,

Now, for negative numbers, the mirror image happens. Of course, we can’t take even roots of negative numbers (square root, fourth root, etc.) but we can take odd roots. For numbers in the –1 < x < 0 range, negative numbers with an absolute value less than one, when we take a root, the value gets closer to –1, and the higher the root, the closer it is to –1. Thus, for these numbers

Thus, the rule works in opposite directions in these two regions, (0 < x < 1) vs. (–1 < x < 0). Both of these regions are included, even with combined statements, so we can give no definitive answer to the prompt question.

Answer = (E)

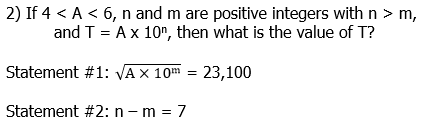

2) Statement #1: Given this statement, we could square 23,100, and that would be some number between 4 & 6 times some power of ten. We don’t actually have to perform that calculation. It’s enough to note that, from this statement, we can determine the value of both A and m. Unfortunately, n remains unknown, and without n, we can’t determine the value of T. This statement, alone and by itself, is insufficient.

Statement #2: This statement tells us nothing about A, and it doesn’t allow us to determine unique values for either n or m. We can’t determine anything with just this. This statement, alone and by itself, is insufficient.

Combined statements: The first statement allows us to determine unique values for A & m. Once we know m, we can use the second statement to find n. Once we know both A & n, we can determine the value of T. Combined, the statements are sufficient. Notice, we can arrive at this conclusion without a single calculation: that’s the ideal of GMAT Data Sufficiency!!

Answer = (C)

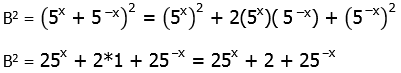

3) First, we need to know the formula for the square of a binomial:

Thus:

Now, we need to recognize that 5 to the x and 5 to the negative x are reciprocals, so their product is one:

Also, by the laws of exponents:

Similarly,

Thus,

Subtract two from both sides, and we have

Answer = (D)

Thus, a & b are in a ratio of 4-to-3. Thus, we could say that a = 4n and b = 3n, for some n. Thus, a + b = 4n + 3n = 7n = 56, so n = 8. Well, a – b = 4n – 3n = n = 8

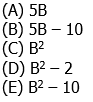

Answer = (B)

Statement #1 tells us that, for some unknown positive integer, N is larger than 1,000,000 and smaller than 10,000,000. Could there be more than one power of 23 in that region? No, because even if N were equal to the lowest possible value in the range, 1,000,000, if we multiply another factor of 23, it would bring us up to 23,000,000, which is above the high end of the range. The ratio of the top end to the bottom end is just 10:1 = 10, which is smaller than 23, so more than one power of 23 cannot possibly fit in this range.

Thus, there can only be one integer value A that puts N in this range. We don’t have to calculate it: it’s enough to know that the information given unique determines the value of A. Thus, this statement, alone and by itself, is sufficient.

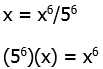

Statement #2 is a tautology. A tautology is a statement that is true by definition, and thus gives no information. The verbal statement “My book is a book” is a tautology: it tells us absolutely nothing useful about that book. The mathematical statement x + 5 = x + 5 is a tautology: that gives us absolute no mathematical information that would allow us to solve for x; in other words, it is true for every single number on the number line.

This statement is a more sophisticated tautology. To understand this, we need to know how to add and subtract powers.

This statement is true for all numbers on the number line, so it contains absolutely no useful information for determining the value of A. This statement, alone and by itself, is insufficient.

Answer = (A)

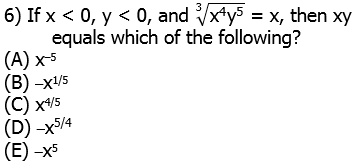

Cube both sides. The cube or fifth power of a negative remains negative, but the fourth power of a negative is positive.

Because we know that x cannot be zero, we can divide by x cubed. Notice that (positive) x-to-the-fourth divided by (negative) x-cubed equals (negative) x.

There’s no direct way to go from this to the product xy. We have to solve for y in terms of x.

Now, we can simply take the fifth root of both sides.

Now, we are in a position to find the product.

Answer = (C)

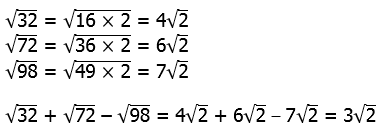

7) For this one, we need to know how to simplify square roots. We can use the formula

Suppose we cleverly factor the number under the square root so that Q is a perfect square: then we could simplify that factor.

Notice that all three numbers under the radical sign are of the form: two times a perfect square. That gives us a big clue to simplifying them.

Answer = (A)

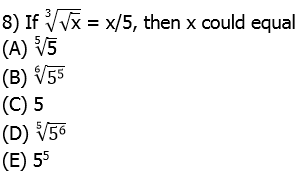

8) Start with the given equation

Cube both sides.

Now, square both sides.

Now, one solution is x = 0, but that’s not listed as an answer. We are looking for a non-zero answer, so if x is not zero, we can divide by x.

Now, take the fifth-root of both sides.

Answer = (D)

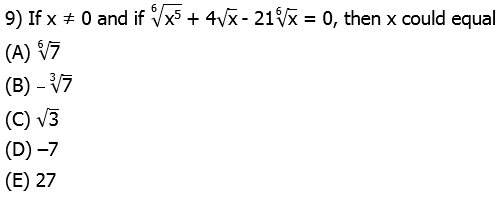

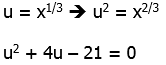

9) With this one, it’s helpful to rewrite the roots as a fractional exponents:

Because x ≠ 0, we can divide all three terms by ![]() . This leaves:

. This leaves:

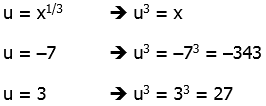

This is now an ordinary quadratic. To see this, use the substitution

(u + 7)(u – 3) = 0

u + 7 = 0 OR u – 3 = 0

u = –7 OR u = +3

We have to be careful here. Here, –7 is a solution for u, but not for x. Now that we have values for u, we have to solve for the corresponding values of x.

The first is not an available answer choice, but the second is answer choice (E).

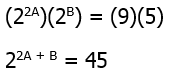

10) Start with the first equation

Square both sides:

Now, multiply this by the second equation:

Answer = (C)

Special Note:

To find out where powers and roots sit in the “big picture” of GMAT Quant, and what other Quant concepts you should study, check out our post entitled:

What Kind of Math is on the GMAT? Breakdown of Quant Concepts by Frequency

Leave a Reply