Master this fundamental GMAT algebra skill, which you will need on test day!

Practice Problems

First, try these practice problems.

1) \(x^2 – 10x – 24 = \)

(A) (x – 4)(x + 6)

(B) (x + 4)(x – 6)

(C) (x – 4)(x – 6)

(D) (x – 2)(x + 12)

(E) (x + 2)(x – 12)

3) If \(6x^2 + x – 12 = (ax + b)(cx + d) \), then |a| + |b| + |c| + |d|

(A) 10

(B) 12

(C) 15

(D) 18

(E) 20

If these are easy for you, you probably have already mastered factoring: kudos to you! If these confuse you, you have found just the post you need.

Terminology

You don’t need to know any of this terminology for the GMAT, but we need it just to talk about these ideas in words.

A binomial is a polynomial with two terms: all five answer choices to question #1 are the product of two binomials. A quadratic is a polynomial with three terms whose highest power is x-squared: the stem of question #1 is a quadratic, and the stem of question #2 is a ratio of two quadratics. To factor a quadratic is to express it as the product of two binomials. Question #1 is a straightforward “factor the quadratic” problem. Question #2 involves factoring both quadratics, in the numerator and in the denominator, and then cancelling a common factor.

Technically, any quadratic could be factored, but often the result would be two binomials with horribly ugly numbers — radicals, or even non-real numbers. You will not have to deal with those cases on the GMAT. We call a quadratic “factorable” if, when you factor it, the resulting equation has only integers appearing. You will only have to factor “factorable” quadratics on the GMAT.

Sometimes, factoring quadratics involves quadratic like that in #3, with a leading coefficient (the coefficient of the x-squared term) is an integer other than 1. These are considerably harder, and you will only see one like this if you are getting most of the math questions correct and the CAT is feeding you one 700-level question after another.

The secret of factoring: FOIL

The best way to understand factoring well is first to understand FOILing well. Suppose we multiply two binomials:

\((x + p)(x + q) = x^2 + qx + px + pq = x^2 + (p + q)x + pq\)

Notice, if we follow the FOIL process forward, then we see two things. First, the middle coefficient, the coefficient of the x term, is the sum of the two numbers. Second, the final term, the constant term with no x, is a product of the two numbers. Right there, that’s the key of factoring. If I want to factor any polynomial of the form \(x^2 + bx + c\), then to factor it, we are looking for two numbers that have a product of c and a sum of b.

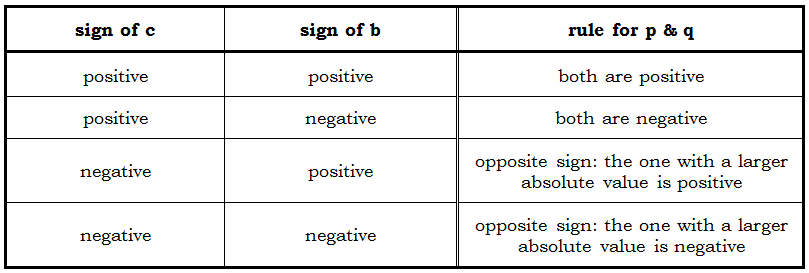

Things get a little complicated when some negative signs are floating around, so here’s a table, for all cases, for the two numbers, p and q, we need to find to factor the quadratic. In the table that follows, b is the coefficient of the x-term, c is the constant term with no x, and both of those are given in the quadratic; p & q are the two numbers we need to factor the quadratic into (x + p)(x + q).

BTW, I highly recommend NOT memorizing the above chart, but rather, thinking it through, and doing FOIL examples for each case, to convince yourself of the patterns and to ingrain them into your memory.

So, for example, suppose we want to factor: \(x^2 – 7x – 18\). Since c = –18 is negative, that means the p & q we want will have opposite sign: one positive, one negative. Since b = –7 is also negative, that means which one, p or q, has the larger absolute value, that one will be negative. We are looking for a bigger negative, and smaller positive, which will have a product of –18 and a sum of –7. One way to think about this is: we need a pair of factors of 18 that have a difference of 7. These two numbers are clearly 9 & 2. Make the bigger one negative: –9 & +2. Those are the numbers we need. Now, stick these into the factoring format:

\(x^2 – 7x – 18 = (x – 9)(x + 2)\)

Voila! Having read this, see if you now can figure out questions #1 & #2 above

Advanced topic: dealing with a leading coefficient

Most GMAT test takers will not see this topic. Only if you anticipating getting the vast majority of questions on the Quant section correct should you even read this section.

Suppose you have to factor something like \(8x^2 – 7x – 18\). This is tricky, because you are looking for four integers: a, b, c, and d, such that \(8x^2 – 7x – 18 = (ax + b)(cx + d)\). The constraints we have are

(i) ac = 8 (both positive)

(ii) bd = –18 (one positive, one negative)

(iii) ad + bc = –7

This is not quite as methodical and left-brain as factoring in the easy case above. This involves a certain amount of number sense and a certain amount of pattern matching. For a & c, the only two possibilities are, in some order, either 2 & 4 or 1 & 8. For b & d, the possibilities for the absolute values are, in some order, either 1 & 18 or 2 & 9 or 3 & 6 — with the understanding that, in whichever one of those pairs we pick, one must be negative and one positive. Eventually, after some experimenting and trial-and-error, we find (8)(–2) + (1)(9) = –7 —- this is the combination we need.

\(8x^2 – 7x – 18 = (8x + 9)(x – 2)\)

If that makes sense, and you feel up to the challenge, try #3.

Summary

Factoring quadratics is such a widely used skill in algebra that you are likely to see something such as Question #1 or #2 on your GMAT. Here’s another practice question, with its own video explanation.

4) http://gmat.magoosh.com/questions/117

Practice problem explanations

1)\( x^2 – 10x – 24 = ??\)

We need two numbers, p and q, which have a product of –24, which means one is negative and one is positive. Their sum is –10, which means the one with the larger absolute value is negative. Let’s go through the factor pairs of 24, in each case making the larger one negative

1 –24 sum = –23

2 –12 sum = –10

That’s the one we want! The pair we want is +2 and –12: they have a product of –24 and a sum of –10.

\(x^2 – 10x – 24 = (x – 12)(x + 2)\)

Answer = E

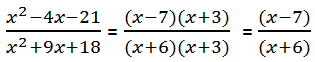

2) For this one, we need to factor both the numerator and denominator. In the numerator, we have x^2 – 4x – 21, so we need two numbers that have a product of –21 and a sum of –4. After a little trial and error, we find the pair that works is –7 and +3, so:

\(x^2 – 4x – 21 = (x – 7)(x + 3)\)

Now, the denominator, x^2 + 9x + 18. We need two positive numbers that have a product of 18 and a sum of 9 — these would be 3 & 6. Thus:

\(x^2 + 9x + 18 = (x + 6)(x + 3)\)

We see that we have a common factor of (x + 3) that will cancel. Now, let’s put the fraction together:

Answer = B

3) This is the hard one, definitely a 700+ level question. We need numbers a, b, c, and d such that

\(6x^2 + x – 12 = (ax + b)(cx + d)\)

This means that ac = 6, bd = –12, and ad + bc = 1. The a & c pair could be (1, 6) or (2, 3), in some order. The absolute values of the b & d pair could be (1, 12) or (2, 6) or (3, 4), and of course, in each case, one of the two would have to be negative. After some trial and error, we find:

\(6x^2 + x – 12 = (2x + 3)(3x – 4)\)

Thus, we see:

|a| + |b| + |c| + |d| = 2 + 3 + 3 + 4 = 12

Answer = B

Leave a Reply