Here are a set of practice GMAT questions about the Cartesian plane.

1) What is the equation of the line that goes through (–2, 3) and (5, –4)?

-

(A) y = –x + 1

(B) y = x + 5

(C) y = –3x/7 + 15/7

(D) y = –4x/3 + 1/3

(E) y = 9x/5 + 33/5

2) The line y = 5x/3 + b goes through the point (7, –1). What is the value of b?

-

(A) 3

(B) –5/3

(C) –7/5

(D) 16/3

(E) –38/3

3) A line that passes through (–1, –4) and (3, k) has a slope = k. What is the value of k?

-

(A) 3/4

(B) 1

(C) 4/3

(D) 2

(E) 7/2

If these problems make your head spin, you have found the right post.

Slope

Slope is a measure of how steep a line is. There is very algebraic formula for the slope, and if you know that, that’s great! If you don’t know that formula, or used to know it and can’t remember it, I will say: fuhgeddaboudit! Here’s a much better way of thinking about slope. Slope is rise over run.

To calculate rise and run, first have to put the two points in order. It actually doesn’t matter which one we say is the first and which one, the second: all that matters is that we are consistent.

The rise is the vertical change — the change in y-coordinate (second point minus first). The run is the horizontal change — the change in the x-coordinate (again, second minus first). Once we have rise & run, divide them, rise divided by run, to find the slope.

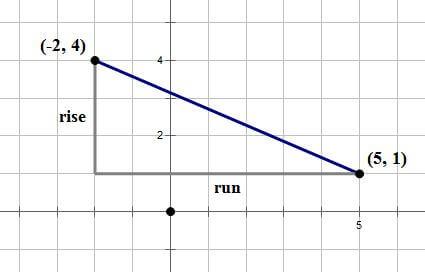

For example, suppose our points are (–2, 4) and (5, 1). For the sake of argument, we’ll say that’s the order — (–2, 4) is the “first” and (5, 1) is the “second.” The rise is the change in height, the change in y-coordinate: 1 – 4 = –3 (notice, we had to do second minus first, which gave us a negative here!) The run is the horizontal change, the change in x-coordinate: 5 – (–2) = 5 + 2 = 7 (remember: subtracting a negative is the same as adding a positive!). Now, rise/run = –3/7 —- that’s the slope. Slope is definitely something you need to understand for the GMAT Quantitative section.

Whenever you find a slope, I strongly suggest doing a rough sketch, just to verify that the sign of the slope (positive or negative) and the value of the slope are approximately correct. Here’s a sketch of this particular calculation:

Your sketch, of course, does not need to be this precise. Even a rough sketch would verify that, yes, the slope should be negative. Again, I highly recommend performing this visual check every time you calculate slope.

Equations in the x-y plane

Let’s get a bit philosophical for a moment. The technical name of the x-y plane is the Cartesian plane, named after its inventor, Mr. Rene Descartes. Although you may have met this sometime in middle school math and may now take it for granted, it is actually a brilliant mathematical device. It allowed for the unification of two ancient branches of mathematics: algebra and geometry. In more practical terms, every equation (an algebraic object) corresponds to a picture (a geometric object). That is a very deep idea.

Equations of lines

A straight line is a very simple picture, and not surprisingly it has a very simple equation. There are a few different ways to write a line, but the most popular and easiest to understand is y = mx + b. The m is the slope of the line. The b is the y-intercept: where the line crosses the y-axis. For any given line, m & b are constants: for a given line, both m & b equal a fixed number. By contrast, x & y (sometimes call the “graphing variables”) do not equal just one thing. This is not the “x” of ordinary solve-for-x algebra. This is a very deep idea — x & y don’t equal any one pair of values; rather, every single point (x, y) on the line, the entire continuous infinity of points that make up that line — every single one of them satisfies the equation of the line. That is a powerful and often underappreciated mathematical idea.

Finding the equation of a line

Sometimes the GMAT will give you the equation of a line already in y = mx + b form. Sometimes, the GMAT give you the line in another form (e.g. 3x + 7y = 22), and you will have to do a little algebraic re-arranging —- essentially, solve for y —- to bring the equation into y = mx + b form. Sometimes, though, as in problem #2 above, they give you two points and ask you to find the equation of a line. Here the procedure. First, find the slope (as demonstrated above). Now, plug the slope in for “m” in the y = mx + b equation, and pick either point (it doesn’t matter which one) and plug those coordinates in for x & y in this equation. This will produce an equation in which everything has a numerical value except for “b” — that means, you can solve this equation for the value of b. Once you know m & b, you know the equation of the line.

Practice

After this introduction, go back and try those practice problems again before reading the solutions below. Here’s another relevant practice question:

4) http://gmat.magoosh.com/questions/821

In the next post, I will discuss midpoints and the issue of parallel & perpendicular lines. See also, the related posts on Distance in the Cartesian Plane, the Quadrants, and the special properties of the line y = x.

Explanation of practice questions

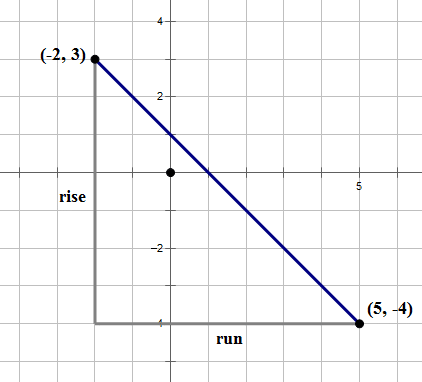

1) Here, we will follow the procedure we demonstrated in the last section. Call (–2, 3) the “first” point and (5, –4), the “second.” Rise = –4 – 3 = –7. Run = 5 – (–2) = 7. Slope = rise/run = –7/7 = –1. Visual check:

Yes, it makes sense that the slope is negative. We have the slope, so plug m = –1 and (x, y) = (–2, 3) into y = mx + b:

3 = (–1)*(–2) + b

3 = 2 + b

1 = b

So, plugging in m = –1 and b = 1, we get an equation y = –x + 1. Answer = A

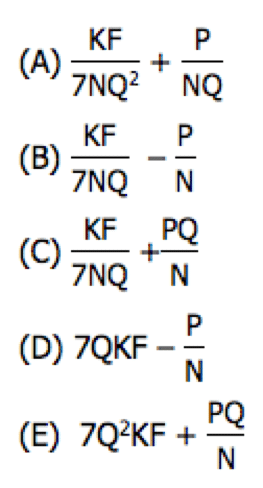

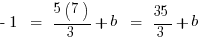

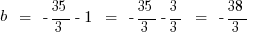

2) Here, we already have the slope, so we just need to follow the second half of the “finding the equation” procedure. Plug (x, y) = (7, –1) into this equation:

Answer = E

3) This is a considerably more difficult one, which will involve some algebra. Let’s say that the “first” point is (–1, –4) and the “second,” (3, k). The rise = k + 4, which involves a variable. The run = 3 – (–1) = 4. There the slope is (k + 4)/4, and we can set this equal to k and solve for k.

k + 4 = 4k

4 = 3k

k = 4/3

Answer = C