Are the Logical Reasoning sections of the LSAT keeping you from reaching your score goals? Not to worry! As with many sections of the LSAT exam, the tricky logic found in LSAT Logical Reasoning question types can be mastered with familiarity and practice.

In other words, one of the best ways to start your journey towards a higher score is getting familiar with the LSAT Logical Reasoning question types—and understanding the method of reasoning you’ll need to use in order to answer them in the given time frame.

Table of Contents

- Which LSAT Logical Reasoning question types are the most common?

- LSAT Logical Reasoning Question Types

- Strengthen Questions

- Weaken Questions

- Flaw Questions

- Inference Questions

- Main Idea/Conclusion Questions

- Paradox Questions

- Parallel Flaw Questions

- Parallel Reasoning Questions

- Principle Questions

- Method of Argument Questions

- Role of Statement Questions

- Evaluate the Conclusion Questions

- Point of Contention Questions

- Point of Agreement Questions

- Assumption Questions

- A Final Word

Which LSAT Logical Reasoning question types are the most common?

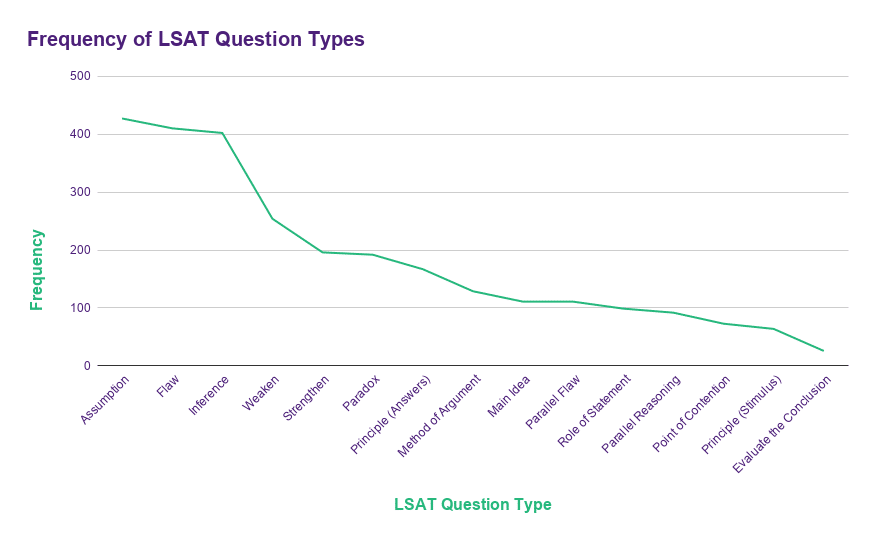

The graph above displays the various LSAT Logical Reasoning question types, ranked by how frequently they appear on the exam. Thus far, the chart includes 55 of the more recent LSAT exams administered over the past 15 to 20 years.

The numbers show that the vast majority of LSAT Logical Reasoning question types are either Assumption, Flaw, or Inference questions. Those three types combined historically represent about 40% of all LR questions. If you add in Strengthen, Weaken, Paradox, and Principle questions, you’ve accounted for over 75% of the questions on the exam.

Due to how frequently they show up, the most common LSAT Logical Reasoning question types deserve more attention in your prep. However, this doesn’t mean you should neglect the other question types. Many question types, such as Main Point/Conclusion, Role, and Method of Reasoning questions, train fundamental skills in Logical Reasoning. Improving at these skills will help your overall logical reasoning ability, so make sure to devote sufficient time to studying all question types.

LSAT Logical Reasoning Question Types Breakdown

Before you can answer any LR questions, you’ll need to know what type of question you’re looking at—and what the correct answer entails. Keep reading to get the breakdown of all the LSAT Logical Reasoning question types!

Strengthen Questions

Strengthen questions ask you to identify possible gaps between the evidence presented in a stimulus and the conclusion drawn, and then narrow those gaps by adding new evidence. The answer choice will present a fact that makes it more likely for the conclusion to be accurate. However, it does not have to make it absolutely certain that the conclusion is correct.

If I said that cats are lazier than dogs because cats sleep 18 hours a day, you could strengthen my argument by saying that dogs sleep only 12 hours a day. That still doesn’t prove that cats are lazier, but it supports the theory that they are.

Show more about Strengthen questions

Below is a list of some of the common ways in which a Strengthen question can be phrased.

- Which of the following, if true, most strengthens the argument?

- Which of the following, if true, adds the most support to the conclusion?

- The conclusion is most strongly supported if which of the following is true?

- Which of the following, if true, argues most strongly for [the conclusion]?

- Each of the following, if true, supports the argument EXCEPT…

- Which of the following would account for the evidence without supporting the conclusion?

Most Strengthen questions will have some form of the phrase “if true” in the prompt. The last example includes this phrase, but also provides an excellent illustration of how well-disguised some Strengthen questions are. In this case, it’s a Strengthen EXCEPT question because four answer choices will support the conclusion and one will not (but won’t necessarily weaken it either).With Strengthen questions, the trick is to identify that the question is asking you to provide a piece of information that is not explicitly stated, but that helps to narrow any gaps between the evidence and the conclusion.

Weaken Questions

Weaken questions ask you to identify possible gaps between the evidence presented in a stimulus and the conclusion drawn, and then widen those gaps by adding new evidence. The answer choice will present a fact that makes it less likely for the conclusion to be accurate. However, it does not have to make it absolutely certain that the conclusion is incorrect.

If I said that eating a donut every morning will make you gain weight because donuts are high in saturated fat and carbohydrates, you could weaken my conclusion by citing a study showing that people who eat donuts have more energy and do more exercise than people who don’t. That doesn’t prove that eating donuts won’t lead to weight gain, but it supports the idea that eating donuts might actually lead to weight loss.

Show more about Weaken questions

Below is a list of some of the common ways in which a Weaken question can be phrased.

- Which one of the following, if true, would most weaken the logic of the argument?

- Which one of the following, if true, most seriously calls into questions the conclusion of the argument?

- Which of the following, if true, most seriously undermines the reasoning in the argument?

- Which of the following, if true, would provide evidence against the conclusion?

- Each of the following, if true, directly undermines the claim that [something is true] EXCEPT…

Most Weaken questions will have the phrase “if true” in the prompt, along with some form of the word “weaken” or “undermine”. However, there are a number of less common forms that appear. With Weaken questions, the trick is to identify that the question is asking you to provide a piece of information that is not explicitly stated, but that calls attention to any gaps between the evidence and the conclusion.

Flaw Questions

Flaw questions ask you to identify an error in the reasoning of an argument.. Typically, this takes the form of a gap between the evidence and the conclusion, similar to Assumption, Strengthen, and Weaken questions. In Flaw Questions, however, the correct answer will be a description of the gap itself, rather than a fact that could help to widen or narrow that gap.

For instance, I could argue that all stone fruits bloom in winter or early spring because my plum tree is blooming right now and it’s February. The gap is between what my plum tree is doing and what “all stone fruits” are doing. However, rather than looking for a fact like, “The apricot tree next door didn’t bloom until June,” we’re looking for a description of the gap. The correct answer will say something like, “The argument assumes that what’s true of one stone fruit must be true of all.”

Show more about Flaw questions

Below is a list of some of the common ways in which a Flaw question can be phrased.

- The argument is most vulnerable to criticism on the grounds that it…

- Which one of the following is an error in the argument’s reasoning?

- A flaw in the reasoning of the argument is that…

- A questionable technique used in the argument is that of…

- The reasoning in the argument is misleading because it…

- Which one of the following most accurately describes [some person]’s criticism of the argument made by [some other person]?

Most Flaw questions will contain the word “flaw,” “vulnerable,” “criticism,” or “questionable.” The last example is very difficult to recognize as a Flaw question. It is asking us to describe a criticism of an argument, and that is the essence of all Flaw questions. Normally, we have to find the Flaw on our own, but in this particular example, the flaw is right there in the text; all we have to do is properly identify it.With Flaw questions, you’ll always be describing the nature of an error, rather than identifying ways to address the error, as you are in Assumption, Strengthen, and Weaken questions.

Inference Questions

Inference questions ask you to determine which answer choice is most likely to be true given only the information provided in the stimulus. These are a bit different than most other Logical Reasoning question types because the stimulus is not actually an argument. Instead, it’s just a string of premises–or facts–that you must assume are true for the purposes of the question.

Show more about Inference questions

For example, an Inference stimulus might tell you that:

- Alaska experiences financial trouble whenever oil prices fall,

- that oil prices fall whenever there is a spike in oil production,

- and that Congress just passed a bill that will result in an increase in the oil supply due to expanded drilling in the Arctic.

Given all of the above: A proper inference is that Alaska will suffer financially.

Now, those of you who know more about the oil industry than I do might argue that Alaska could do something to force higher prices or to make itself less reliant on oil revenue. That may be true, but it’s irrelevant in this question because we can only use the information provided to make our inference. In this case, that information makes it clear that Alaska suffers when the oil price drops, the oil price drops when supplies increase, and supplies are about to increase. We don’t really care about the real-world accuracy of the facts provided. We just need to pretend they’re the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and roll with it.

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which an Inference question can be phrased.

- Which one of the following answer choices is most strongly supported by the information above?

- Which one of the following can be properly inferred from the statements above?

- If all of the above statements are true, then which one of the following must also be true?

- The statements above, if true, most logically support which of the following conclusions?

- Which one of the following most logically completes the sentence above?

Most Inference questions will include some form of the word “inference” or some form of “most strongly support(ed).” However, the real key to recognizing an Inference question is paying attention to what’s supporting what. In Inference questions, the statements in the stimulus will support an answer choice. In most other Logical Reasoning question types, the answer choices will support (or weaken, or parallel) an argument in the stimulus. Just remember that an Inference question is asking you to determine a new fact based solely on the ones explicitly provided in the stimulus.

Main Idea/Conclusion Questions

Main Idea questions are straightforward: they ask you identify the conclusion of the argument. Each answer choice will summarize a different statement in the stimulus, and you have to determine which ones are the premises and which one is a new idea drawn from those premises.

Show more about Main Idea/Conclusion questions

Below is a list of some of the common ways in which a Main Idea question can be phrased.

- Which of the following most accurately expresses the overall conclusion of the argument

- Which of the following most clearly states the main idea of the argument?

- In the argument, the statement that [some premise] is offered in support of the claim that…

Most Main Idea questions have the structure shown in the first example. Almost all of them ask about the “conclusion” or the “overall conclusion”. The last example is a rare illustration of how Main Idea questions might be disguised. With Main Idea questions, the trick is to remember that you are being asked to point out something explicitly stated in the argument. All you have to do is differentiate between evidence and conclusion.

Paradox Questions

Paradox questions ask you to provide an explanation for a pair of facts that seem to contradict each other. These are similar to Assumption questions in that each answer choice will introduce a new piece of information that could affect how you interpret the facts in the stimulus. The difference between Paradox and Assumption questions, however, is that in a Paradox question there is no argument being made. The stimulus is just a couple of facts.

Show more about Paradox questions

A Quick Example

The highest mountain on earth is Everest, which rises 29.029 feet above sea level. However, Everest is not the tallest mountain on earth. That title belongs to Mauna Kea, which only rises 13,796 feet above sea level.

Again, there is no argument presented in the stimulus above. It’s just a couple facts about some tall mountains. The paradox lies in the fact that the tallest mountain on earth is not the highest mountain on earth. Why? Because Mauna Kea extends another 19,700 feet below the surface of the ocean, making its total height over 33,000 feet. The correct answer would need to provide this information to explain the seeming contradiction in the facts presented.

So, the key to Paradox questions is to find a piece of information that just makes sense. Kind of a relief, right?

More Resources for Paradox Questions

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which a Paradox question can be phrased.

- Which one of the following, if true, most helps to resolve the apparent discrepancy in the information above?

- Each of the following, if true, helps to resolve the apparent paradox in the statements above EXCEPT…

- Which one of the following, if true, most helps to explain why…

- Which one of the following, if true, most contributes to a resolution of the discrepancy above?

Paradox questions are one of the easiest types to spot on the LSAT. They almost always include some form of “resolve” or “explain” along with “apparent,” “paradox,” and/or “discrepancy.” There aren’t many uncommon variations in phrasing, and these question types tend to appear more in the first half of a section, meaning they are on average a bit easier than most other question types.

Parallel Flaw Questions

Parallel Flaw questions provide you with a short scenario that involves a faulty chain of reasoning. Your task is to identify the answer choice containing the same flaw as the original. The trick here is to remember that all or most of the answer choices will contain flawed logic, but you are looking for the one that is flawed in the same way as the stimulus. That can be a bit confusing. Paired with the fact that you have to map out the original scenario and those of all five answer choices, this is a beast of a question type. It will probably take more time than any other question type, so along with Parallel Reasoning questions, it’s a good candidate to leave for the end. Luckily, there will only be one per Logical Reasoning section.

Show more about Parallel Flaw questions

A Quick Example

Every time I take the bus, I’m late to work. Yesterday, I was late to work. Therefore, I must have taken the bus.

If you already see the flaw, you’re halfway there. Let’s map it out briefly. If I take the bus (A), I’m late (B). That can be written as “If A, then B.” Yesterday, I was late (B), so I must have taken the bus (A). In other words, “B, so A” (which is the same thing as saying “if B, then A”). If you’re not already familiar with the basics of contrapositives, you should get caught up on them now. Otherwise, you probably noticed that we reversed our original terms (A and B), but didn’t negate them. That’s faulty logic. So, we need to find an answer choice that makes the same mistake. It starts with “If A, then B,” and uses that alone to conclude “B, so A.”

That’s a quick look at a Parallel Flaw question. The key thing to remember is that most if not all of the answer choices will be flawed, but only one of those flaws will match the original. That said, the sentences in the correct answer choice don’t have to appear in the same order as they did in the stimulus. They just need to be the same pieces, so that you can construct a similarly flawed argument by rearranging the order of the statements, if necessary.

More Resources for Parallel Flaw Questions

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which a Parallel Flaw question can be phrased.

- The pattern of flawed reasoning exhibited by the above argument most closely parallels that exhibited by which one of the following?

- Which one of the following contains flawed reasoning that most closely parallels that in the argument above?

- Which one of the following arguments is vulnerable to criticism most similar to that which can be applied to the argument above?

- The argument above exhibits flawed reasoning most similar to the flawed reasoning in which one of the following?

Parallel Flaw questions, as you might have guessed, contain elements of both Parallel Reasoning and Flaw Questions. Therefore, they will often feature language like “parallel” or “similar” paired with language like “flawed reasoning” or “vulnerable to criticism.”

This question type, along with Parallel Reasoning questions, tends to be found in the latter half of most Logical Reasoning questions. This is a clue to its difficulty level. Parallel Flaw questions are typically among the most difficult questions in a section, so it’s a great idea to leave them until the end and tackle them only once you’ve picked all the low-hanging fruit.

Parallel Reasoning Questions

Parallel Reasoning questions provide you with a short scenario that involves a chain of reasoning, and then they ask you to select an answer choice containing a different scenario with a similar chain of reasoning. These are easily some of the most time-consuming questions on the exam since they basically require you to work through six different stimuli (the actual stimulus plus each of the five answer choices).

On the bright side, there is rarely more than one of these questions in a given Logical Reasoning section, meaning you’ll probably only have to do two of them on the exam (however, you’ll also probably have to do two Parallel Flaw questions, which can be equally as time-consuming).

Show more about Parallel Reasoning questions

A Quick Example

If Paulina plays goalie in the upcoming soccer match, her team will win. If her team wins, they will continue to the regional championships next month. Therefore, if Paulina plays goalie in the upcoming match, her team will play in the regional championships.

This is a particularly simple example of a parallel reasoning scenario. Here we have three basic if/then statements lined up nicely in the proper order. If A (playing goalie), then B (winning). If B (winning), then C (regional championships). So by linking our two statements together, we get the conclusion: if A (playing goalie), then C (regional championships). The correct answer will mimic this chain of reasoning: If A, then B. If B, then C. So if A, then C.

It’s worth noting two things at this point. First, the correct answer must consist of conditional reasoning similar to the original stimulus. Imagine an answer choice that reads, “Margaret is going to the movies and then to the nightclub. After the nightclub, she’s going home. So Margaret is going home after the movies.” This would be incorrect, because even though it follows the A, B, C chain we constructed above, there are no conditional statements involved. It also leads to a bizarre result that is technically correct, but certainly misleading. Second, remember that the correct answer choice may not resemble the scenario in the stimulus at all. Don’t be thrown off by that. The only thing that matters is the logic upon which it’s constructed.

More Resources for Parallel Reasoning Questions

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which a Parallel Reasoning question can be phrased.

- The pattern of reasoning displayed above most closely parallels that in which one of the following arguments?

- Which one of the following is most similar in its reasoning to the argument above?

- The logical structure of which one of the following is most similar to that of the argument above?

- The argument above most closely parallels the reasoning in which one of the following?

Parallel Reasoning questions almost always contain some form of the word “parallel” or “similar.” They also typically refer to an argument’s structure, pattern, or reasoning. These questions are similar in form to Parallel Flaw questions, except that the latter will specify that the original argument (the stimulus) contains flawed reasoning, as does the correct answer. There’s really no difference in how you treat these two question types, as long as you accurately map the logic of the passage (accurate or not) and find the matching answer choice.

Principle Questions

There are two variations on Principle questions in the LSAT Logical Reasoning section. The first of these LSAT Logical Reasoning question types presents you with a scenario and asks you to identify a principle that justifies the decision made in the scenario. The second of these Logical Reasoning question types presents you with a principle and asks you to select a scenario in which that principle is applied most accurately.

Show more about the first type of Principle questions

A Quick Example

Jimmy receives a weekly allowance of $20 from his parents in exchange for mowing the lawn, taking out the trash, and feeding the dog. This summer, Jimmy is going to spend a month at a camp in the mountains, so he will not be able to perform his regular chores during that period. His parents should still pay him his allowance for the month that he’s at camp.

This scenario is every kid’s dream come true. He doesn’t have to do any work, but he still gets paid. What could the justification be for this decision? Well, maybe Jimmy’s parents are thinking of his allowance like a salary. In that case, his time at camp is like paid vacation. The principle might sound something like, “Rather than an hourly wage or a payment for services rendered, an allowance is a weekly payment to a child in recognition of that child’s ongoing efforts to help around the house.”

So, in this type of Principle question, we are trying to locate an answer choice that provides a rational reason for the behavior described in the stimulus. The key to identifying these is to remember that the stimulus will be a scenario, whereas the answer choices will contain the principles.

More Resources for Principle Questions (First Type)

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which this type of Principle question can be phrased.

- Which one of the following principles, if valid, most helps to justify the decision by [Jimmy’s parents to pay him his allowance while he’s away at camp]?

- The situation as described above most closely conforms to which one of the following principles?

- The argument most closely conforms to which one of the following generalizations?

- Which one of the following general propositions, if valid, most supports the argument above?

Principle questions (both types) will almost always feature language like “principle,” “generalization,” or “proposition.” They also feature some elements of Parallel Reasoning language, since we’re looking for an answer choice that describes the logic used in the stimulus. It’s usually pretty easy to spot these questions, but they can range in both difficulty and number. That means you may see only one per section, or you may see three spread out within a single section.

Show more about the second type of Principle questions

A Quick Example

Any new tax implemented by a government must be for a specific purpose, and all revenue collected from that tax must be directed exclusively toward achieving that purpose.

Here we have our principle, and now we need to look for a situation in which that principle is accurately applied. There are tons of possibilities, so let’s just take one bad example and one good example. First, the bad answer: “Gorblandia has enacted a new sales tax because the government is worried that it won’t have enough revenue this year to cover its expenses. All the money from the sales tax will go to covering expenses and to providing tax credits for international businesses that want to establish headquarters in Gorblandia.” Okay…this tax sucks. First of all, covering expenses is a pretty weak “specific purpose.” Second, it’s unclear how much of the tax revenue will actually cover expenses versus how much will be spent trying to lure corporations to the country. Nope, nope, nope.

Here’s a good answer: “Chaconia has proposed a new tax on cigarettes that is intended to deter youth from smoking both by raising the cost of cigarettes and by funding a new public school program aimed at educating youth about the risks of smoking.” Excellent. There is a specific purpose (deterring youth from smoking), and all the revenue will go to fund a program that serves said purpose. This is a nice, clean application of our principle to a real scenario.

So, in this type of Principle question, we are trying to locate an answer choice that describes a scenario in which someone correctly followed the principle given in the stimulus. The key to identifying these is to remember that the stimulus will be a principle, whereas the answer choices will contain scenarios.

More Resources for Principle Questions (Second Type)

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which this type of Principle question can be phrased.

- The principle above, if valid, most strongly supports which one of the following arguments?

- Which one of the following describes a scenario in which [some decision was made] according to the principle stated above?

- Which one of the following is an application of the principle cited above?

- Which one of the following most closely conforms to the proposition offered above?

This second type of Principle question can be a bit time consuming because you have to read through five different scenarios. The answer choices tend to be lengthy. Fortunately, this is a relatively uncommon question type, with rarely more than one or two instances per exam. If timing is an issue for you, this might be a good candidate to skip and return to at the end.

Method of Argument Questions

Method of Argument questions ask you to analyze the structure of an argument the same way you might analyze the composition of a painting or the plot of a movie. You’ll have to focus on how the argument was designed and which rhetorical tools were used. By rhetorical tools, I mean elements of an argument like supporting examples, counterexamples, facts, expert opinions, or hypothetical questions. These are the building blocks of arguments, and mapping them out quickly will help you answer Method of Argument questions.

Show more about Method of Argument questions

A Quick Example

Sea levels will rise faster than previously expected. Scientists have discovered that the largest glacier in Antarctica, is melting at three times the rate predicted ten years ago. That glacier alone could raise sea levels by up to two meters if it were to melt entirely. A leading climate journal has recently expressed concern that glacier melt in the Andes is also contributing to rising sea levels as rivers in the region expand dramatically from the increased glacial runoff.

This argument starts with the conclusion: sea levels will rise faster than we thought. It is followed by the main supporting premise: a huge glacier in Antarctica is melting faster than we expected. Finally, it’s further supported with an expert opinion: a journal thinks rivers in the Andes are making things worse. So, the method of argument is to use expert testimony and scientific evidence to support a prediction.

As with all Logical Reasoning questions, we’re not overly concerned with the real-world accuracy of the statements made. LSAT questions tend to contain accurate information, but that’s irrelevant. We want to ignore the accuracy of the argument and instead focus on its logical structure. Rather than asking whether a given statement is true or false, focus on whether it supports or contradicts the conclusion. That’s the key to nailing Method of Argument questions.

More Resources for Argument Questions

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which a Method of Argument question can be phrased.

- The [Speaker] uses which one of the following methods to craft his response to the critics’ claims?

- The argument above proceeds by…

- [Speaker #2] responds to [Speaker #1] by… (this counts as Method of Argument because it’s asking how the second half of the stimulus is different from the first half)

- The argument above does which one of the following?

- Which one of the following describes a technique used by [Speaker] in the argument above?

Most Method of Argument questions will include some form of “method” or “technique.” However, there are some tricky forms like the third one listed above, which only appears in questions with dialogues. Method of Argument questions can be difficult to distinguish from Role of Statement questions, but that’s nothing to worry about because you use a similar process to answer both. Just ask yourself whether the question is asking about a specific sentence (Role of Statement) or the overall structure of the stimulus (Method of Argument).

Role of Statement Questions

Role of Statement questions ask you to pick the answer choice that best describes the function of (typically) one sentence within the argument.

Show more about Role of Statement questions

Take the following argument as an example:

Staring at a computer screen all day can damage your eyes. However, computer programs to exercise your eyes while at work are becoming more popular. Therefore, staring at computer screens will be less likely to cause eye damage in the future.

The second sentence is 1) a piece of evidence that 2) supports the conclusion by 3) countering the first piece of evidence. This is a detailed description of why the author included that sentence in the argument. The author started with a fact that was contrary to his conclusion, so he needed something in the middle to get from point A to point B.

More Resources for Role of Statement Questions

Below is a list of some of the common ways in which a Role of Statement question can be phrased.

- Which of the following most accurately describes the role played in the argument by the claim that…

- The claim that [some claim] plays which one of the following roles in the argument?

- Which one of the following most accurately describes the relationship between [Person 1]’s statements and [Person 2]’s statements?

- Which one of the following is the most accurate evaluation of the statement that…

Most Role of Statement questions will have the word “role” in them, though “relationship” or “function” appears occasionally as well. The second to last example could be interpreted as a Method of Argument question since it addresses the entire stimulus. However, it’s asking us to look at how each statement individually functions. This illustrates the similarity between Role of Statement and Method of Argument questions: the former is basically a more detailed version of the latter.

The last example above is a very unusual structure and might be hard to recognize as a Role of Statement question. With Strengthen questions, the trick is to identify that the question is asking you what function a particular sentence plays in the argument. Why is it there? What is it accomplishing?

Evaluate the Conclusion Questions

Evaluate the Conclusion questions ask you to determine what information would be necessary in order to determine the accuracy of a conclusion. The answer choices will pose different questions, the answer to which may or may not affect the conclusion. The correct answer will present a question to which you must know the answer in order to decide whether you agree with the conclusion.

Show more about Evaluate the Conclusion questions

Below is a list of some of the common ways in which an Evaluate the Conclusion question can be phrased.

- Which one of the following would be most useful to know in order to evaluate the logic of the argument above?

- The answer to which of the following questions would most assist in the evaluation of [some person]’s argument?

- Which one of the following considerations is LEAST helpful in determining the validity of the claim made by [someone in the argument]?

Most Evaluate the Conclusion questions will have some form of “evaluate” in them, but not all of them. The last example above is from a question that requires you to find an answer choice that does not affect the argument. With Evaluate the Conclusion questions, keep in mind that you are not being asked to make an evaluation; instead, you’re merely being asked to identify a question you would need to answer before making that evaluation.

Point of Contention Questions

Point of Contention questions provide you with a short dialogue and ask you to identify a point on which the two speakers disagree. As with Point of Agreement questions, this is often much harder than it sounds. The speakers will probably not explicitly state opposite opinions on any one particular point. Instead, the first speaker will express an opinion on a topic and somehow rationalize that opinion. The second speaker will then typically focus on the rationalization used by the first speaker rather than on the central point being made.

Show more about Point of Contention questions

A Quick Example

Matheson: Ted Williams is the greatest baseball player of all time. After all, he’s the only player to achieve a batting average over .400 in more than 85 years.

Rogers: But Nap Lajoie had the highest batting average of all-time, and Barry Bonds hit far more home runs than Ted Williams did during his career. If you only look at one of their statistics, either of those two players could also be considered the greatest baseball player of all time.

In a question like this, there’s sure to be answer choice that says that Matheson and Rogers disagree over whether Ted Williams is the greatest baseball player of all time. Unfortunately, that answer would be incorrect. We don’t know who Rogers think is the greatest of all time; we just know that he believes batting average alone isn’t enough to make that determination. So, it’s more accurate to say that Matheson and Rogers disagree over whether Ted William’s record batting average alone makes him the greatest player of all time. More generally, we could say that they disagree over whether any one statistic is sufficient to make such a judgement.

More Resources for Point of Contention Questions

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which a Point of Contention question can be phrased.

- [Speaker #1]’s and [Speaker #2]’s statements most strongly support the claim that they would disagree with each other on which one of the following?

- The point at issue between [Speaker #1] and [Speaker #2] is whether…

- An issue in dispute between [Speaker #1] and [Speaker #2] is…

- Which one of the following most accurately expresses a point of disagreement between [Speaker #1] and [Speaker #2]?

- Based on [Speaker #1]’s and [Speaker #2]’s comments, it can be concluded that they disagree that…

Point of Contention questions can come in many different forms, but they will all contain some kind of language denoting conflict between the speakers. Common words to find are “disagree,” “dispute,” “issue,” and “contention”. It’s also worth noting that Point of Contention questions are going to look a lot like Point of Agreement questions, so read them carefully and make sure you don’t answer the opposite of what the question’s asking.

Point of Agreement Questions

Point of Agreement questions provide you with a short dialogue and ask you to identify a point on which the two speakers agree. This might sound easy at first, but they’re never going to give you an answer choice that is explicitly stated by both speakers. Instead, you’ll have to do a little inferring to figure out where there’s agreement and where there’s disagreement between the two speakers. If you’re uncomfortable with this question type, you’ll be happy to know that this is extremely uncommon among LSAT Logical Reasoning question types. Fewer than 10 of them have appeared on the 77 most recent official LSATs.

Show more about Point of Agreement questions

A Quick Example

Mathilde: The forests in France are artificial. That’s why all the trees grow in perfectly straight rows and columns. You can see it clearly when you drive by on the highway.

Franco: I’ve seen the rows of trees you mention. However, those are areas where people have reclaimed marshland or replanted land that was cleared sometime in the past. Those are not the real forests of France.

Do Mathilde and Franco agree that the forest of France are artificial? Probably not. It seems as though Franco is arguing that France has real forests elsewhere in the country. Do they agree that the rows of trees planted by humans are forests at all? It doesn’t sound like it. Mathilde calls them forests, but Franco implies that these aren’t actually forests. Do they agree that there are places in France where the trees grow in straight rows? Yes. Mathilde clearly states this and Franco says he’s seen them before. This is a simple example, but hopefully it illustrates how some answer choices can sound awfully tempting, but are not fully supported by the text.

More Resources for Point of Agreement Questions

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which a Point of Agreement question can be phrased.

- [Speaker #1]’s and [Speaker #2]’s statements most strongly support the claim that they would agree with each other on which one of the following?

- Based on [Speaker #1]’s and [Speaker #2]’s comments, it can be concluded that they agree that…

As mentioned above, Point of Agreement questions are exceptionally uncommon among LSAT Logical Reasoning question types, so there aren’t many examples of the language used to phrase them. However, it seems logical that you’ll see some form of “agree” in there somewhere. Otherwise, they should look very similar to Point of Contention questions, which are much more common and so provide a wider variety of possible phrasings for you to study.

Assumption Questions

Assumption questions ask you to find a gap between the evidence presented in a stimulus and the conclusion drawn.

Take a look at this necessary assumption question: There are thousands of apple trees on a certain farm and then argue that the farm must make most of its money selling apples. The evidence relates to the number of apple trees whereas the conclusion is about the relative value of those trees. So, there’s a gap between number and value that must have been bridged by making some assumption about the relationship between those two elements. The assumption is that the farm doesn’t have any other sources of income that are more profitable than its thousands of apple trees. That may be true or it may be false. We don’t ultimately care about the actual accuracy of the assumption. All we care about is this: if the assumption is false, does the conclusion hold?

Show more about Assumption questions

Below is a list of some of the common forms in which an Assumption question can be phrased.

- Which of the following is an assumption that is required by the argument?

- The argument requires the assumption that…

- The conclusion can be properly drawn if which one of the following is assumed?

- The conclusion is properly drawn if which one of the following completes the argument?

- [Person 2]’s response most strongly supports the claim that he understood [Person 1]’s argument to be that…

Most Assumption questions will have some form of the word “assume” in the prompt. However, the last two examples above illustrate how this is not always the case. With Assumption questions, the trick is to identify that the question is asking you to provide a piece of information that is not explicitly stated, but that must be true in order for the argument in question to make sense.

A Final Word on LSAT Logical Reasoning Question Types

There you have it! Each and every one of the LSAT Logical Reasoning question types you could see on the official exam.

Now that you’re familiar with the characteristics of these LSAT Logical Reasoning question types, what are your next steps? As you work through LSAT practice tests, do your best to identify which type of question you’re looking at. Knowing this unlocks the key to the right answer—as well as the wrong answer choices!

Once you’ve completed a full LR section, return to this post to analyze the LSAT Logical Reasoning question types you tend to get wrong, then focus on those for the next few days of study. What’s stumping you—causation, correlations, the argument’s conclusion? Answering lots of LR questions, then going back to analyze their LSAT Logical Reasoning question types—is key to unlocking a higher score in this section!

This post was written with contributions from our writers Kevin and Rachel.