Although the name may seem nondescript – after all, what does it mean to ‘remove’ someone, anyway? – the Indian Removal Act was the forcible and violent dispossession of indigenous people’s land in the southeastern United States. The consequences of this legislation are felt to this day. Keep reading to get an overview of what this policy meant for in United States history – and what it means today.

What was the Indian Removal Act?

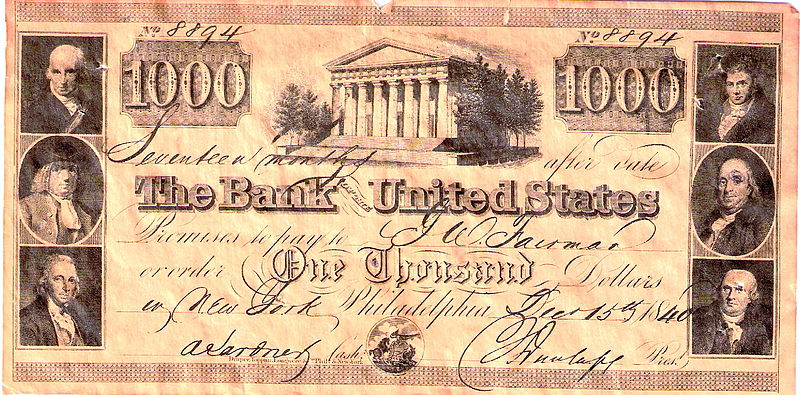

On May 28, 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law. This Act allowed the President to “exchange” lands west of the Mississippi (that the young country had received a few decades before as a result of the Louisiana Purchase) for the land that indigenous people occupied within existing state boundaries.

It’s important to remember that, in 1830, indigenous people were not considered citizens of the United States; these individuals had their own sovereign governments, and their nations intersected and crossed over state lines.

Throughout the 1810s, the United States began encroaching on indigenous territory. In some cases, the government attacked these lands under the guise of protecting citizens’ property; that property happened to be in the form of slaves that ran to freedom in Spanish Florida, occupied primarily by the Seminole tribe. Whatever the justification, things came to a head in 1823.

So what happened in 1823?

In this year, the Supreme Court declared, in Johnson v. McIntosh, that private citizens could not purchase land from indigenous people because the indigenous people could not hold titles to the land (titles are basically like a receipt or proof of purchase when what you are purchasing is a relatively large asset that cannot be turned into cash quickly, like a plot of land). This was because, as the legal reasoning went, indigenous people’s right to the land was second to the U.S.’s “right to discovery”.

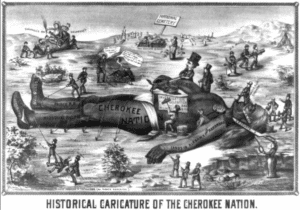

Native Americans did not take this action laying down. In fact, one group – the Cherokees – sued the United States government in the landmark case known as Cherokee Nation v. the State of Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832). I will come back to these cases a little later.

When did the Indian Removal Act take effect?

It is difficult to pen down one date; remember, this piece of legislation is removing thousands of people from their homes. That cannot happen overnight. However, through illegitimate treaties and force, the United States government removed some 46,000 indigenous people by 1837 – primarily from the Choctaw and Creek nations – west of the Mississippi.

The Cherokee nation was more difficult to remove. In 1838, nearly 16,000 individuals in the Cherokee nation remained on their land. At bayonet point, the government marched these individuals to their new homes in present-day Oklahoma. Roughly 4,000 Cherokees died in this forced march, which has been memorialized as the Trail of Tears.

Caricature of the legal battles the Cherokee endured to try and keep their homeland. Source here.

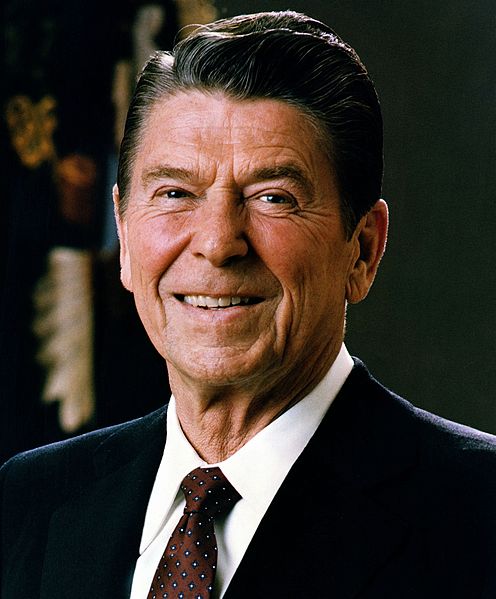

In 1830, President Jackson began his statement in the State of the Union with these words:

“It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation. Two important tribes have accepted the provision made for their removal at the last session of Congress, and it is believed that their example will induce the remaining tribes also to seek the same obvious advantages.”

Can you explain the court cases: Cherokee Nation v. the State of Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia?

Yes! But, as always, a brief background is important first.

In 1830, the state of Georgia passed a law that stated that individuals residing in Cherokee territory must obtain a state license. This was a problem because the Cherokee Nation was a separate political entity; it would be like asking for individuals living in Canada to get the United States permission first.

Several missionaries, including Samuel Worcester, refused to get such a license, and they were prosecuted in the Georgia courts. Worcester appealed that decision all the way to the Supreme Court. Surprisingly, the Supreme Court agreed with Worcester, stating that Georgia law did not have authority in Indian territory. (This ruling was surprising because the Court had previously ruled in Cherokee Nation v. the State of Georgia that it did not have the authority to hear the case, since the Cherokee Nation was not a foreign nation, but rather, a sovereign political entity residing within U.S. state boundaries.)

However, President Jackson did not listen to the Supreme Court, showing the limits of the power of judicial review.

What is the legacy of the Indian Removal Act?

The biggest legacy of the Indian Removal Act is the reservation system that exists today. Reservations, often located in areas with few natural resources and isolated geographically, have higher rates of various social ills, primarily due to high unemployment.

What types of questions will I be asked on the APUSH exam about the Indian Removal Act?

Select the ONE best response. Source here.

When Indian removal was completed in 1837,

A. every Indian west of the Mississippi River was gone.

B. every Indian tribe east of the Mississippi was gone.

C. the Indians were relocated in reservations much like the tribal lands they left.

D. the Indians were far enough removed from whites where they would not face further encroachments.

E. only elements of the Seminoles and Cherokees remained.

Correct Answer:

E; The Trail of Tears occurred from 1838-1839, and the Seminole conflict would last much longer.