The focus of this blog post will be for you to practice the skill of identifying changes and continuities throughout APUSH with one theme in mind: party politics.

We know that getting all the details about what happened in U.S. history (let alone explaining the significance of those events) can be hard. That’s why we have created this series of posts that gives you a brief overview of one theme at a time, along with tips to help you think about patterns of change and continuity. Ready to dive in? Let’s go!

A Brief Overview of Political Parties

Before we dive into the theme for this post, it’s important for me to point out two things.

- This is not AP US Government, and this blog post will be looking at the development of political parties in the United States as a historical phenomenon.

- Because of #1, this blog post will not get into the nuances of each political party.

Now that we have gotten those two things out of the way, let me try to orient you to what this blog post will be doing. In order to look at the development of political parties in the United States as a historical phenomenon, we will be examining three historical periods.

- The Early Republic

- The Age of Jacksonian Democracy

- Political Machines

- The Civil Rights Movement

The astute student (which I am sure you are!) likely noticed that there are several events missing; in any survey of history, there likely will be!

However, I want you to think about how the four themes above might change if I chose different events to highlight for the development of political parties. Furthermore, as always, keep a close eye on multiple themes that might be important in the events that I do highlight.

APUSH Themes: Party Politics

1. The Early Republic

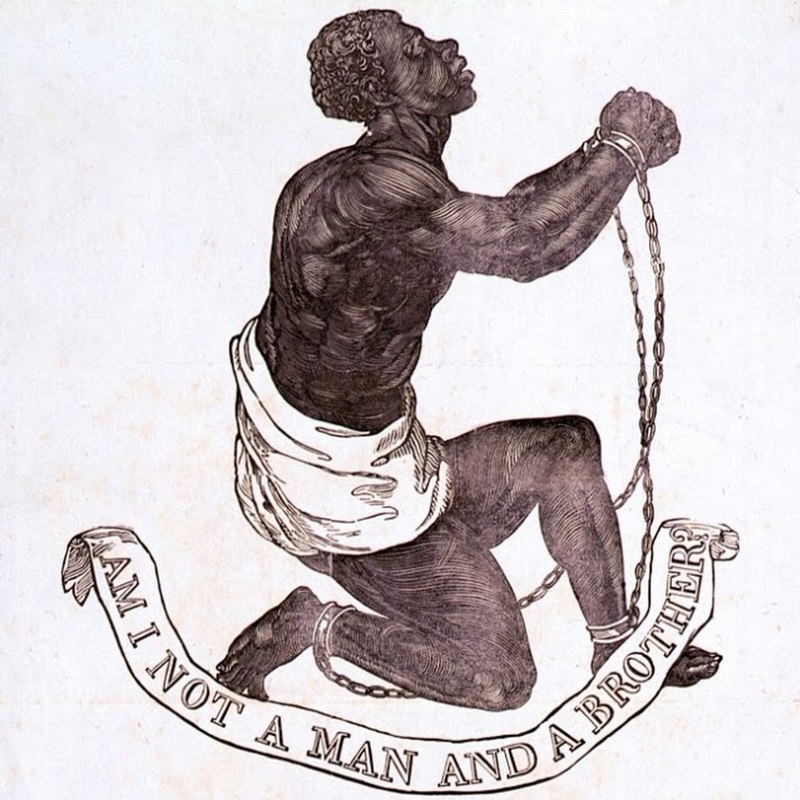

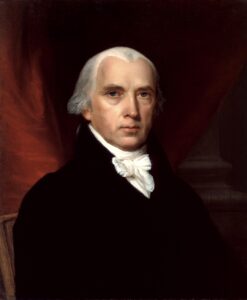

Portrait of James Madison, writer of the Federalist 10 (Source)

If you’ve read any of the Federalist papers, you likely know that there were a lot of conflicting opinions about how to run the country once the United States actually became a country. This sentiment is, perhaps, best articulated by James Madison in Federalist 10. Here, he writes:

- “AMONG the numerous advantages promised by a well-constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction…By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community. There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: the one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects.”

Madison goes on to explain that the goal of a country is to control factions where they exist. Eliminating them altogether would require tyranny and, even then, human nature would bend people towards factioning off.

And how did Madison propose controlling the effects of factions? See if you can parse it out here:

- “The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens…”

Essentially, Madison is saying that the only way to protect against an overwhelming majority faction to stomp on the rights of the minority factions is to have so many options to choose from that no one faction gains too much power. This is totally in line with a classical liberal ideology, and it’s totally not what we have today. So what gives?

Well, political parties are really good at organizing people and, in a republic where individuals vote on their representatives, organizing people is key to gaining political power. Perhaps no one knew that better than our seventh President, Andrew Jackson.

2. The Age of Jacksonian Democracy

The era of Jacksonian Democracy would dramatically change the political landscape in America. How? Three words: Expand. The. Base.

Andrew Jackson’s election to President in 1828 would give him the title (often debated) of “the people’s president.” And it’s easy to see why that happened. Let’s examine the changing voter qualifications in one state: New Jersey.

| Time | Text |

|---|---|

| 1776 | All inhabitants of this colony of full age, who are worth fifty pounds (basic unit of currency in use at the time)…and have resided within the county in which they claim to vote for twelve months immediately preceding the election, shall be entitled to vote. |

| 1807 | …no person shall vote in any state or county election for officers in the government of the United States, or of this state, unless such person be a free, white male citizen of this state, of the age of twenty-one years, worth fifty pounds…, and have resided in the county where he claims a vote, for at least twelve months immediately preceding the election. |

| 1844 | Every white male citizen of the United States, of the age of twenty-one years, who shall have been a resident of this state one year, and of the county in which he claims to vote five months…shall be entitled to vote. |

Source: Edsitement Lesson on Andrew Jackson

I mean, the expansion isn’t perfect, but going from owning 50 pounds in 1776 (the equivalent in 2018 of nearly $8,000, as a low estimation) to just being a (white, male, at least 21-year-old) citizen is a big step.

How did this happen?

A lot of things had to go right, including the expansion of newspapers and the increased political maneuvering of many individual actors. But the basic idea is that, through practices such as campaigning—which included what we would consider grassroots organizing, like door-to-door canvassing and meet-and-greets with the politicians—Presidential elections became national news. And, with this expanded voter base, political parties became even more important in assisting the effort to get individuals elected.

3. Political Machines

It can be argued that the strength of political parties would reach their zenith in what came to be known as “political machines.” Broadly speaking, political machines were controlled by bosses or a small group of individuals who directed the party’s members to get votes for the favored candidate; the members were, in turn, rewarded for their loyalty through the spoils system.

One of the most infamous political party bosses was William “Boss” Tweed. Political machines had their detractors, of course. Take, for instance, the work of political cartoonist Thomas Nast below.

Tweed depicted in Harper’s Weekly, October 21, 1871 (Source)

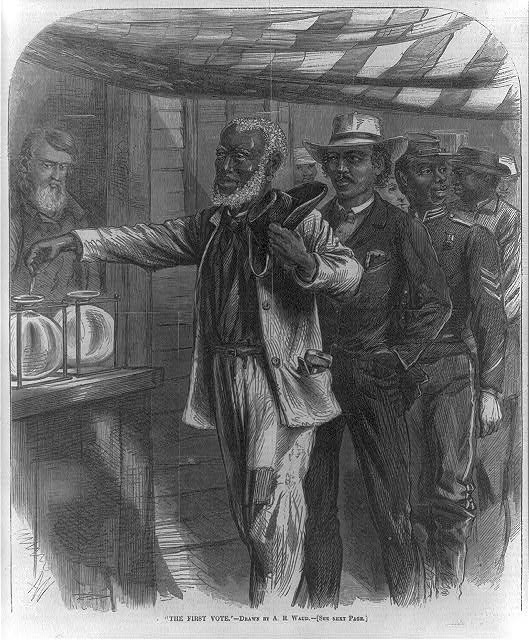

4. The Civil Rights Movement

But how does any of this help explain the striking differences that we see over time in the sway certain political parties have in different parts of the country?

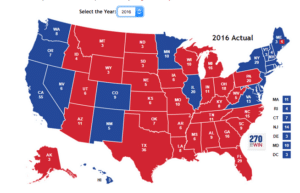

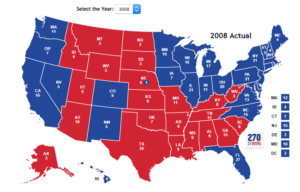

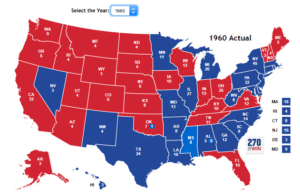

Source: 270 to Win

The historical maps above are, from top to bottom, the results of the 2016, 2008, and 1960 elections.

Some individuals look to the legislation of the Civil Rights Movement to explain the dramatic switch and then dramatic consistency. I say, check out this excellent video to help you get a sense of how the Civil Rights Movement influenced the switch we see in the maps above.

So what should I do with all this history on APUSH Themes: Party Politics?

Well, there are several things you can do with it! If you were to write a change over time essay based on the information presented here, you might highlight:

- The ways in which factions were present from the country’s founding;

- How broadening the base of who was allowed to vote shifted the importance of political parties as organizational tools; and

- The changing power of political parties over time.

There are so many themes you can use to help you make sense of this important topic. Do you have any other ideas? Reply in the comment section below!