In the following probability problems, problems #1-3 function as a set, problems #4-5 are another set, and problems #6-7 are yet another set. The scenarios are all similar in a set, and the answer choices for those problems in the same set are the same. What is going on there? Do all questions in the same set have the same answer? Do all have different answers? What is happening?

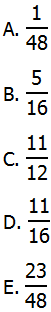

1) In a certain game, you perform three tasks. You flip a quarter, and success would be heads. You roll a single die, and success would be a six. You pick a card from a full playing-card deck, and success would be picking a spades card. If any of these task are successful, then you win the game. What is the probability of winning?

2) In a certain game, you perform three tasks sequentially. First, you flip quarter, and if you get heads you win the game. If you get tails, then you move to the second task. The second task is rolling a single die. If you roll a six, you win the game. If you roll anything other than a six on the second task, you move to the third task: drawing a card from a full playing-card deck. If you pick a spades card you win the game, and otherwise you lose the game. What is the probability of winning?

3) In a certain game, you perform three tasks. You flip a quarter, and success would be heads. You roll a single die, and success would be a six. You pick a card from a full playing-card deck, and success would be picking a spades card. If exactly one of these three tasks is successful, then you win the game. What is the probability of winning?

The following information accompanies questions 4-5

Johnson has a corporate proposal. The probability that vice-president Adams will approve the proposal is 0.7. The probability that vice-president Baker will approve the proposal is 0.5. The probability that vice-president Corfu will approve the proposal is 0.4. The approvals of the three VPs are entirely independent of one another.

4) Suppose the Johnson must get VP Adam’s approval, as well as the approval of at least one of the other VPs, Baker or Corfu, to win funding. What is the probability that Johnson’s proposal is funded?

(A) 0.14

(B) 0.26

(C) 0.49

(D) 0.55

(E) 0.86

5) Suppose Johnson must get the approval of at least two of the three VPs to win funding. What is the probability that Johnson’s proposal is funded?

(A) 0.14

(B) 0.26

(C) 0.49

(D) 0.55

(E) 0.86

The following information accompanies questions 6-7

Johnson has a corporate proposal. The probability that vice-president Adams will approve the proposal is 0.6. If VP Adams approves the proposal, then the probability that vice-president Baker will approve the proposal is 0.8. If VP Adams doesn’t approve the proposal, then the probability that vice-president Baker will approve the proposal is 0.3.

6) What is the probability that one of the two VPs, but not the other, approves Johnson’s proposal?

(A) 0.12

(B) 0.24

(C) 0.28

(D) 0.48

(E) 0.72

7) What is the probability that at least one of the two VPs, approves Johnson’s proposal?

(A) 0.12

(B) 0.24

(C) 0.28

(D) 0.48

(E) 0.72

Solutions will come at the end of this blog.

Probability blogs

Here are some previous blogs on probability

2) The Probability “At Least” Question

3) Probability and Counting Techniques

5) Probability DS Practice Questions

Each of the first four have a few practice questions, and the fifth article has 8 DS questions, so combined with the seven here, that’s a great deal of probability practice!

A review of rules

One important idea in probability is mutually exclusive (a.k.a. “disjoint”). Two events are mutually exclusive if they both can’t happen at the same time, if the very fact that one happens completely precludes the other from happening. For example, on a single coin toss, the results H and T are mutually exclusive. On a single die roll, the six numbers on the die are mutually exclusive.

If events F and G are mutually exclusive, then

P(F and G) = 0

and

P(F or G) = P(F) + P(G)

The first equation expresses mathematically what we expressed in words: it’s impossible for outcomes F & G to occur at the same time. The second rule is the pure form of the rough probability idea that “OR means add” — that rule is approximately true most of the time, but exactly true when the two events are mutually exclusive.

If events A and B are just general events, not mutually exclusive, then

P(A or B) = P(A) + P(B) – P(A and B)

That is the generalized OR rule, a very important rule.

Another important idea in probability is the idea of independent. Two events are independent if whether one happens has absolutely no bearing on whether the other happens; in other words, if we are told the outcome of one event, the fact that this outcome occurred gives us absolutely no information that would help us predict whether the other event will occur. In tossing coins, the separate coins are independent. In rolling dice, the separate dice are independent. In the real world, two absolutely unrelated things would be independent. Consider these two events:

Event A = the New York Mets win on a particular day

Event B = the Nikkei (the Japanese stock index) goes up on a particular day

Those two have absolutely no influence on one another, and even if we are given explicit information about the outcome of one, that would give us absolutely no insight into the outcome of the other.

If each of two variables is a numerical variable that could take a range of numerical values, then a synonym for “independent” would be “completely uncorrelated.” If two variables are correlated, then having information about the value of one allows you to make an informed prediction about the value of the other. If two variables are independent, then knowing the value of one doesn’t give us the foggiest idea of what the other could be.

If events X and Y are independent, then

P(X and Y) = P(X)*P(Y)

This rule is the pure form of the rough probability idea that “AND means multiply” — that rule is approximately true most of the time, but exactly true when the two events are independent. Notice, for independent events, we can simplify the generalized OR rule:

P(X or Y) = P(X) + P(Y) – P(X)*P(Y)

Those rules will get you through a great deal of the probability on the GMAT. BUT, what if we need an AND rule for two events that are not independent? What would be the “generalized” version of the AND rule for any two events, not just events that are independent. In order to talk about that, we need to introduce a new idea.

It’s worthwhile also mentioning — the conditions “mutually exclusive” and “independent” are special case scenarios. They are the opposite of common: they are relatively rare. Never make it your default assumption that either is true unless the question makes clear that it must be the case.

Conditional probability

This is a term that, like many math terms, will not explicitly appear on the GMAT, and the notation I will show, standard in many probability textbooks, will not appear on the GMAT. Nevertheless, the idea of conditional probability does appear on the GMAT.

The notation we use is P(A|B). Event A is the main focus: we are interested whether or not A occurs. Event B is some kind of condition we impose: the idea is, we will pretend that we live in a world in which Event B is always true — under those conditions, what is the probability of A? P(A|B) is a “conditional probability”, a probability when we impose the condition of B. The notation P(A|B) is read “the probability of A, given B.”

Here are a few examples. Suppose

A = on a given day in Berkeley, CA, it rains

B = on a given day in Berkeley, CA, there are no clouds in the sky.

Here P(A) would be the probability that here in Berkeley we get rain on a randomly selected day; that would be approximately 0.10 or 0.15. By contrast, if we impose the condition “no clouds”, then the conditional probability, P(A|B), would have to be zero: how could it possibly rain when there are no clouds? This is an example of a condition lowering a probability; in the next example, the condition will elevate the probability.

Here’s another example, more socially relevant. Suppose

A = a randomly selected felony defendant is convicted

B = the defendant is African-American

P(A) looks at all folks in the USA accused of and tried for felony, and regardless of any individual factors (race, age, evidence, crime, etc.) just looks at: what percent, overall, are convicted? According to the BJS, this percent is P(A) = 0.68. In a world of perfect fairness and equality, P(A) and P(A|B) would equal exactly the same thing — in other words, a person’s race would play absolutely no role in whether that person were convicted of a felony. Most regrettably, in America in 2013, 148 years after the end of the US Civil War, 45 years after the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., racism still has a large effect on American society and an overwhelming effect on the criminal justice system; in other words, P(A|B) > P(A). Conditional probability is not just a mathematical idea: it has profound social and moral implications for all kinds of issues of justice and fairness in the real world.

On a more mathematical note, notice if events X and Y are independent, then whether Y occurs or not should have absolutely no bearing on whether X occurs. In other words, for independent events X & Y, P(X|Y) = P(X).

The generalized AND rule

Now that we have discussed conditional probability, we can discuss the generalized AND rule.

If events A and B are two general events, not mutually exclusive, not independent, then, as a general rule:

P(A and B) = P(A)*P(B|A)

P(A and B) = P(B)*P(A|B)

Either one of these is the generalized AND rule. Notice that AND still means multiply, though what we multiply here is a little different from what was multiplied in the special case with independent events.

For example, suppose we are going to pick two cards from a full 52-card deck, without replacement, and we want to know the probability of picking two heart-cards. The phrase “without replacement” means when we pick the first card, we put it aside and do not return it to the deck, so that the second card is picked from a deck of only 51 cards. That changes the probability. The words “without replacement” always means the choices are NOT independent, because the outcome of the first choice has a big influence on the outcome of subsequent choices. For this example, let

A = first choice is a heart-card

B = second choice is a heart-card

There are four suits in a full deck, and each suit is equally represented, so P(A) = 1/4. Let’s think about P(B|A). If the first card was a heart-card and it was not replaced, that means the second choice is made from a deck of 51 cards that has 13 of the other three suits but only 12 heart-cards. Thus, P(B|A) = 12/51 = 4/17, and P(A and B) = (1/4)*(4/17) = 1/17

The generalized AND rule is often used in sequential tasks such as this, in which there are earlier choices or trials, and the outcomes of these have various effects on later choices or trials. The generalized AND rule is most often not applicable in a more side-by-side choice, in which all the choices are available at the outset.

Summary

If you understand everything in this post, you are a GMAT Probability pro. If you had some insights while reading, you may want to give the seven problems at the top another look before reading the solutions below.

Here’s another probability question:

8) http://gmat.magoosh.com/questions/1038

If you would like to add anything or ask a clarifying question about anything I have said, please let know in the comments sections.

Practice problem solutions

1) In this scenario, winning combinations would include success on any one task as well as any combination of two or three successes. In other words, there are several cases that constitute the winning combinations. By contrast, the only way to lose the game would be unsuccessful at all three tasks. Let’s use the complement rule.

P(lose game) = P(quarter = T AND dice ≠ 6 AND card ≠ spades)

= (1/2)*(5/6)*(3/4) = 5/16

P(win game) = 1 – P(lose game) = 1 – (5/16) = 11/16

Answer = (D)

Curious about why you can’t simply add P(A) + P(B) + P(C) to solve Problem #1? See the extended discussion in the blog comments below. 🙂

2) In this scenario, there are several routes that would lead to winning the game. The only route that leads to losing the game is the route in which all three tasks are unsuccessful. We can do this precisely as we did the previous problem.

P(lose game) = P(quarter = T AND dice ≠ 6 AND card ≠ spades)

= (1/2)*(5/6)*(3/4) = 5/16

P(win game) = 1 – P(lose game) = 1 – (5/16) = 11/16

Answer = (D)

3) This is very tricky. We have to think of three cases.

Case One: success with coin, no success with die or card

P(coin = H AND die ≠ 6 AND card ≠ spade) = (1/2)*(5/6)*(3/4) = 15/48

Case Two: success with die, no success with coin or card

P(coin = T AND die = 6 AND card ≠ spade) = (1/2)*(1/6)*(3/4) = 3/48

Case Three: success with card, no success with die or coin

P(coin = T AND die ≠ 6 AND card = spade) = (1/2)*(5/6)*(1/4) = 5/48

The winning scenario could be Case One OR Case Two OR Case Three. Since these are joined by OR statements and are mutually exclusive, we simply add the probabilities.

Answer = (E)

4) We will use the abbreviation A = VP Adams approves, B = VP Baker approves, and C = VP Corfu approves.

P(funding) = P(A and (B or C)) = P(A)*P(B or C)

We can multiply because everything is independent of everything else. First look at P(B or C). These are not mutually exclusive, so we need to use the generalized OR rule:

P(B or C) = P(B) + P(C) – P(B and C)

Because B & C are independent, we can multiply to find P(A and B)

P(B or C) = (0.5) + (0.4) – (0.5)*(0.4) = 0.9 – 0.2 = 0.7

Now, multiply by P(A)

P(funding) = P(A)*P(B or C) = (0.7)*(0.7) = 0.49

Answer = (C)

5) For this one, we have to consider four different cases

P(A and B and (not C)) = (0.7)*(0.5)*(0.6) = 0.21

P(A and (not B) and C) = (0.7)*(0.5)*(0.4) = 0.14

P((not A) and B and C) = (0.3)*(0.5)*(0.4) = 0.06

P(A and B and C) = (0.7)*(0.5)*(0.4) = 0.14

These four are mutually exclusive and are joined by OR, so we add them.

P(funding) = 0.21 + 0.14 + 0.06 + 0.14 = 0.55

Answer = (D)

6) We will use the abbreviation A = VP Adams approves and B = VP Baker approves. We will consider two cases:

Case #1: Adams approves and not Baker

P(A and not B) = P(A)*P(not B|A) = (0.6)*(0.2) = 0.12

Case #2: Baker approves and not Adams

P(not A and B) = P(not A)*P(B|not A) = (0.4)*(0.3) = 0.12

These two cases are mutually exclusive and joined by OR, we add them.

P(only one VP approves) = 0.12 + 0.12 = 0.24

Answer = (B)

7) Here, the combinations (A and not B), (not A and B), and (A and B) all lead to approval of the proposal. The only one that doesn’t is the complement (not A and not B).

P(not A and not B) = P(not A)*P(not B|not A) = (0.4)*(0.7) = 0.28

P(at least one) = 1 – P(not A and not B) = 1 – 0.28 = 0.72

Answer = (E)

Leave a Reply